Part III

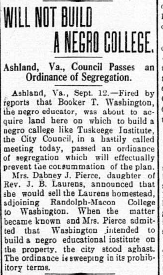

As quickly as the segregation

ordinance was passed in 1912, it was challenged the next month.

On October 27th, John

Coleman, a black entrepreneur and native Ashlander, purchased a home on Henry

Clay Street in the town. At that time, there was already an

established black neighborhood in Ashland, just north of Randolph-Macon

College, called Berkleytown. It was a hub of

activity with stores, a hotel, and restaurants, and the first black school in Hanover County would be built there in 1950

under pressure for the country to provide “separate but

equal educational opportunities.”

John Coleman purchased his small

piece of property for $500 and he paid cash to the Commissioner of Revenue

in Hanover County. The deed book where the sale is recorded notes that it was a small piece of

property situated on the south side of Henry Clay Street, between Snead and James Street-

not in the black neighborhood of Berkleytown.

There

were no street numbers used then, and the property is described as being 27 ½

feet wide by 190 feet deep. When Coleman purchased the property, there was

a black person renting the home, which had been grandfathered under the ordinance.

Ashland’s law specifically stated that it was fine for a black person to

own a home, but they could not reside in that home if the majority of people

living on that block were of the opposite race. Coleman did have some

relatives who lived about two blocks away from the Henry Clay house, so he

could have just simply been moving closer to family.

There are no indications that he

bought the home as a challenge to the ordinance.

At some

point between October 27th of 1911 and October 14th, 1912 John Coleman had

decided to move into the home, because on October 14, 1912, a summons was given

to the town sergeant to deliver to Coleman, ordering him to appear before Mayor

Henry Ellis at 4:00 PM that same day and to pay a $20 fine for the violation of

segregation ordinance. Mr. Coleman was actually charged $20 for the

violation, and $1.80 for “costs,” but it was noted that he asked for an appeal

and was granted one. For that he had to pay $45 “recognizance” fee.

Clearly, Coleman had the means to pay the fine, but his concerns were

with the principal of the law.

The next month, in November of 1912, the Ashland Town Council voted to form a

committee to search for a lawyer to defend the segregation ordinance as

challenged by John Coleman, and they would eventually hire James E. Cannon, of

Richmond, who would go on to become the City Attorney for Richmond in 1923.

The lawyer that Coleman hired to defend his right to live on Henry

Clay Street was Callom B. Jones, Jr, the 25 year old lawyer who also served on

the Ashland Town Council and had voted in favor of passing the segregation

ordinance. John Coleman and Callom Jones were close in age, and both had

lived in Ashland all their lives, so it is very likely that they knew each

other prior to this professional relationship.

When Callom Jones, Jr., served on the Ashland Town Council, he was briefly

appointed interim mayor when there was a gap between, and the question stands,

how could he vote to approve the ordinance and then spend four years attacking

the credibility of the law? Jones was 24 years old when he first served

on Council, a young lawyer living at home with his parents, just down the

street. The rest of the members of Council were his parents’

contemporaries- all white men, all having known Jones from when he was a

child. It would may have been incredibly difficult to vote against these

older town leaders, especially for a 24 year old who was just beginning to

understand his convictions.

Four months later, in March of 1913, the committee that had been appointed by

the town council reported that they had detained Mr. James E. Cannon for a fee

of $150. When the case of Ashland v. Coleman went before Judge Chichester

of Hanover County on September 16th, 1913, Callom Jones had lined up seven

reasons that the segregation ordinance was unconstitutional:

1. A

public trust cannot be delegated or assigned at will.

2. [The

segregation ordinance] will create a petty legislative body in every city

street with jurisdiction over this branch of municipal affairs.

3.

The

Town Council cannot abdicate its legislative powers vested in it by the state.

4.

The

use of one’s property is as much a property as the property itself.

5.

The

ordinance is unequal, unreasonable, oppressive, partial and is discriminating.

6.

The

ordinance is a violation of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States.

7.

The

condemnation of the use of property by a body known as the “greater number of

which are white, etc.,” on a street, is not the due process of law.

Jones argued that by passing the ordinance,

the Town Council violated the power that had been given to them by the state,

and referenced several other cases that supported this. By leaving the

designation of whether a street was a “white” street or a “black” street to the

other residents of that street, that the Town had effectually abdicated its power;

thereby leaving the decision to the other homeowners. He also argued that

by having one set of property owners on a street decide about whether another

property owner can live on the street, that

those majority property owners are taking away the private property rights of

the other person (whom they are asking to leave the block.) They have

control over a piece of property that they have no right to have control over.

The people who have 2/3rds ownership of the block now have power over the

people who have 1/3rd. Jones stated that

the Town abdicated its power of authority by allowing those streets to decide.

John Coleman was denied the lawful use of his property by 2/3rds of the

other property owners on Henry Clay St.

In his defense of the town, lawyer James

Cannon had argued that the town was well within its rights as the General

Assembly of Virginia had passed legislation in March of 1912 (six months after

Ashland passed their ordinance) allowing all towns and cities in the state to

enact segregation laws to keep the races separate. He also argued that

the town council was charged with preserving the public peace; the public

safety and order, and that keeping the races separate was the natural way to

keep everyone calm and happy. This was the general consensus of the era,

as many newspaper articles also wrote about the need to keep blacks and whites

separated in all aspects of their daily lives, except, interestingly, in cases

of blacks working as servants in the homes of whites. The segregation

ordinance in both Ashland and Richmond made exceptions for this. Carolyn Hemphill, the current president of

the Hanover Black Heritage Society asked, incredulously, “They would let black

people live in your house, take care of your children, cook your meals, but

they wouldn't let them live down the street?”

In his ruling on the case, Judge Chichester

further commented on the General Assembly act, stating that even though the

Ashland ordinance had been passed six months prior to the General Assembly Act,

that the town was still acting within its jurisdiction because the ordinance

was an effort to preserve the public morals, an argument that was often used to

promote racial segregation: “The central idea of the ordinance under

consideration seems very manifest. It is to prevent too close association

of the races, which association results, or tends to result, in breaches of the

peace, immorality and danger to health.” He also argued that the

ordinance did not violate the 14th Amendment to the Constitution because it

restricted the residence of whites and blacks equally. He concluded that

the town of Ashland had full authority to pass the ordinance and declared it

valid. Coleman’s appeal was denied.

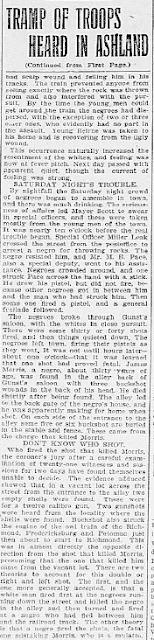

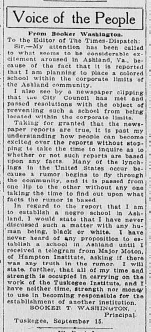

The

Thursday, September 18th, 1913 edition of the Richmond Times-Dispatch newspaper

carried news of the hearing on the front page: “Opinion Upholds Segregation

Law.” The city of Richmond was interested in the news from Hanover County

because there were six cases that were pending over the Richmond segregation

ordinance. Richmond City Attorney H.R. Pollard was quoted as saying, “As far as

I know, this is the first ruling of its kind in Virginia. It is of the

utmost importance and has a direct bearing on the cases now pending against the

city…”

Besides

the quote from the city attorney, there are several circumstances which point

to Ashland v. Coleman as being the first time that a black man had challenged a

segregation ordinance. In the court records obtained from Hanover County,

Callom Jones cited several other cases related to the power of municipal

corporations and the ability for the majority of homeowners on a street to

decide if a billboard should be erected, or a stable to be built, but no cases

involving discrimination over the color of a person’s skin.

At the November 13th regular council meeting,

it was recorded that “Mayor Ellis reported that the Segregation Ordinance

passed by the Town of Ashland had been confirmed by Judge Chichester, but that

the attorney for John Coleman, the defendant in the case, had noted an appeal.”

More than a year later, on October 12th, 1914, the minutes of the

Ashland Town Council approved the payment of $250.00 to James Cannon for him to

represent the town in the appeal case pending before the Virginia Court of

Appeals. The next month, they also approved the hiring of attorney H.R.

Pollard to assist in the appeals case.

Pollard was the City Attorney of Richmond at the time, and he would also

write an amicus curae on behalf of the City of Richmond for the US Supreme

Court Case of Buchanan v. Warley.

In

September of 1915, Coleman’s case was joined together with the case of Mary

Hopkins v. City of Richmond, who was arrested for renting an apartment on a

street that had mostly white residents, and brought before the Virginia Court

of Appeals. In a statement published

earlier that year in the Richmond Planet Newspaper (African-American), H.R.

Pollard wrote that “the unwonted persistency with which many of the leaders

among the colored people in this country have resisted the application of the

basal principal involved in this legislation is almost pathetic.” The rulings

in Hanover and Richmond that supported the segregation ordinances were upheld

by the Court of Appeals, and in the days ahead, those “pathetic” black leaders

would take their case to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In this

early part of the 1900s, segregation ordinances were gaining popularity across

the southern half of the United States. The pendulum of Reconstruction had

swung in the other direction and Jim Crow laws had begun to spread west to

Kentucky, Oklahoma, and Missouri. The National Association for the Advancement

of Colored People was founded in 1909, and by 1913 had hired a full-time lawyer

to help fight against racist legislation. Backed by large support in

Louisville, Kentucky, the NAACP chose this municipality to stage its fight. The

case that would eventually appear before the US Supreme Court, would be

Buchanan v. Warley, a carefully staged court battle between two people chosen

by the NAACP to challenge the segregation ordinance in that city.

The

visibility of that case was heightened by the use of black ministers who coordinated

their Sunday sermons (called, “Segregation Sundays”) to preach on the evils of

Jim Crow laws. William Warley, the president of the Lousiville NAACP, and

Charles Buchanan, a white real estate agent, coordinated the sale of a piece of

property in an area of Louisville where the majority of the residents were

white. Warley entered into a contract to purchase the home, and then

refused to pay based on the inability for him to be able to occupy the

home. Buchanan sued him for breach of

contract. The Louisville ordinance was

supported by the district courts, and appealed to the Kentucky Court of

Appeals, where it was also upheld.

Buchanan

v. Warley was heard before the US Supreme Court in April of 1917, with attorney

Moorefield Storey arguing that segregation laws violated the Constitutional

rights of black citizens. Storey was a white, New England lawyer, whose

family were dedicated abolitionists. He

was the founding president of the NAACP, as well as a practiced constitutional

lawyer and former president of the American Bar Association. In his

arguments before the Supreme Court, Storey argued that the ordinances were

discriminatory to both whites and blacks, that a “discrimination against one

race in violation of the Constitution is not less repugnant because another

race is also discriminated against,” and the court agreed with him. In writing

for the unanimous court, Associate Justice William Day stated that, “property

is more than the mere thing which a person owns. It is elementary that it

includes the right to acquire, use, and dispose of it. The Constitution protects these essential

attributes of property.” The Court ruled that all segregation ordinances were

unconstitutional and ordered that they be removed from all municipal policy.

The Richmond Planet newspaper wrote of the ruling, “God bless the Supreme

Court of the United States, Republicans and Democrats, Jew and Gentile.

We have always believed that God in his own time would make the crooked

ways straight…”