The Segregation Ordinance

Part I

Cleaning Up

The town of Ashland, Virginia was a thriving community in 1911. Randolph-Macon

College had established itself on the grounds of the old Slash resort over forty year earlier

and the school continued to grow. The college was a main employer for the town, and a

center of activity: many local homes served as boarding houses for students and staff,

and businesses on both sides of the tracks served the students. Despite being a Methodist

institution, the college hosted many dances in the Henry Clay Inn, and welcomed young

women from the town to attend. There had been a great fire twenty years earlier that had

destroyed many shops along the tracks, but those had been rebuilt and more businesses

had moved to town.

The Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac railroad had added a second rail at the

turn of the century, and there was a continual stream of train traffic through the town.

News traveled quickly by rail, along with the mail cars, and speed with which newspapers

could be printed and distributed accelerated the delivery of information. Ashland had a

town newspaper, the Hanover Herald, but news from Ashland could also be found in larger

newspapers like the Richmond Dispatch and the Alexandria Gazette (two cities connected to

Ashland by rail).

In 1911, town leaders were mostly concerned with sanitation and controlling the spread

of disease. The town of Ashland had tried to form a company to install underground pipes

to bring water and septic service to the town, but the company had suffered from poor

management and had declared bankruptcy. Most town council meetings were spent trying

to find ways to revive the Ashland Water Company, and passing ordinances designed to

keep away diseases, such as typhoid fever, diphtheria, and tuberculosis. Ever worried about

cleanliness, the town mandated that every house had to be inspected once a month by the

town health inspector, and that stables had to be cleaned out twice a month in the summer

and once a month in the winter.

In early September of 1911, Mrs. Miriam Pierce returned to her father’s home across the

street from Randolph-Macon College (pictured above). Her father, the Reverend J. B. Laurens

(affectionately known as “Uncle Larry”) had been an esteemed Methodist minister and

a professor at the college. He was the founder of the Rosebud Missionary Society and a

popular writer of Methodist doctrine. He died in 1894, and in 1903, the Rosebud Society

honored him with a large granite monument in the Ashland’s Woodland Cemetery.

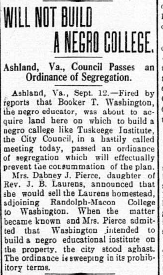

On September 12th, 1911, the Tuesday evening edition of the Alexandria (VA) Gazette

newspaper carried a front page story with the headline, “Will Not Build a Negro College.”

The two short paragraphs read:

Part I

Cleaning Up

The town of Ashland, Virginia was a thriving community in 1911. Randolph-Macon

College had established itself on the grounds of the old Slash resort over forty year earlier

and the school continued to grow. The college was a main employer for the town, and a

center of activity: many local homes served as boarding houses for students and staff,

and businesses on both sides of the tracks served the students. Despite being a Methodist

institution, the college hosted many dances in the Henry Clay Inn, and welcomed young

women from the town to attend. There had been a great fire twenty years earlier that had

destroyed many shops along the tracks, but those had been rebuilt and more businesses

had moved to town.

The Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac railroad had added a second rail at the

turn of the century, and there was a continual stream of train traffic through the town.

News traveled quickly by rail, along with the mail cars, and speed with which newspapers

could be printed and distributed accelerated the delivery of information. Ashland had a

town newspaper, the Hanover Herald, but news from Ashland could also be found in larger

newspapers like the Richmond Dispatch and the Alexandria Gazette (two cities connected to

Ashland by rail).

In 1911, town leaders were mostly concerned with sanitation and controlling the spread

of disease. The town of Ashland had tried to form a company to install underground pipes

to bring water and septic service to the town, but the company had suffered from poor

management and had declared bankruptcy. Most town council meetings were spent trying

to find ways to revive the Ashland Water Company, and passing ordinances designed to

keep away diseases, such as typhoid fever, diphtheria, and tuberculosis. Ever worried about

cleanliness, the town mandated that every house had to be inspected once a month by the

town health inspector, and that stables had to be cleaned out twice a month in the summer

and once a month in the winter.

In early September of 1911, Mrs. Miriam Pierce returned to her father’s home across the

street from Randolph-Macon College (pictured above). Her father, the Reverend J. B. Laurens

(affectionately known as “Uncle Larry”) had been an esteemed Methodist minister and

a professor at the college. He was the founder of the Rosebud Missionary Society and a

popular writer of Methodist doctrine. He died in 1894, and in 1903, the Rosebud Society

honored him with a large granite monument in the Ashland’s Woodland Cemetery.

On September 12th, 1911, the Tuesday evening edition of the Alexandria (VA) Gazette

newspaper carried a front page story with the headline, “Will Not Build a Negro College.”

The two short paragraphs read:

Ashland, Va., Sept 12 - Fired by reports that Booker T. Washington,

the negro educator, was about to acquire land here on which to build

a negro college like Tuskegee Institute, the [Town] Council, in a hastily

called meeting today, passed an ordinance of segregation which will

effectually prevent the consummation of the plan.

the negro educator, was about to acquire land here on which to build

a negro college like Tuskegee Institute, the [Town] Council, in a hastily

called meeting today, passed an ordinance of segregation which will

effectually prevent the consummation of the plan.

Mrs. Dabney J. Pierce, daughter of the Rev. J. B. Laurens, announced

that she would sell the Laurens homestead, adjoining Randolph-Macon

College to Washington. When the matter became known and Mrs. Pierce

admitted that Washington intended to build a negro educational institution

on the property, the city stood agast. The ordinance is sweeping in its

prohibitory terms.

More details were revealed on an inside page of that same paper:

“Residents of Ashland are up in arms over a report that the Laurens

homestead, one of the finest in Ashland, is to be converted into a branch

of the Tuskegee Institute for Negroes. At the City Council’s session last

night, a segregative ordinance was framed. Mrs. Pierce a descendant of

the Laurens, who practically has abandoned the old homestead, returned

a few days ago and began cleaning up the place. When asked what she

was going to do, the answer came promptly that she was contemplating

selling it to Booker T. Washington, who would establish a preparatory

branch of the negro college there. Meanwhile, Ashland, not knowing

where the report is true or not, continues to boil and rail.”

homestead, one of the finest in Ashland, is to be converted into a branch

of the Tuskegee Institute for Negroes. At the City Council’s session last

night, a segregative ordinance was framed. Mrs. Pierce a descendant of

the Laurens, who practically has abandoned the old homestead, returned

a few days ago and began cleaning up the place. When asked what she

was going to do, the answer came promptly that she was contemplating

selling it to Booker T. Washington, who would establish a preparatory

branch of the negro college there. Meanwhile, Ashland, not knowing

where the report is true or not, continues to boil and rail.”

The Richmond Times-Dispatch also published a story about the Tuskegee rumor on that

same day, titled, “College Scheme Will Be Blocked.”

“Segregation Ordinance Introduced in Ashland- Will Be Adopted Today

(Special to the Times-Dispatch)

Ashland, Va., September 11th- At a meeting of the City Council of

Ashland held to-night, a segregation ordinance was introduced that

will be formally adopted at a special meeting to be held tomorrow

afternoon.

Ashland held to-night, a segregation ordinance was introduced that

will be formally adopted at a special meeting to be held tomorrow

afternoon.

The ordinance, with modifications to meet local conditions, is based

on the Richmond ordinance, and in general terms it follows along the

lines of that measure.

on the Richmond ordinance, and in general terms it follows along the

lines of that measure.

It is believed that the prime cause for the introduction of the ordinance

at this time, is the report recently in circulation that the Laurens

homestead, a desirable location in the center of town, and near the

campus of Randolph-Macon College, was to be purchased and converted

into a branch of the Tuskegee Institute for Negroes. On the Laurens

grounds at present is a small-two story frame building and the entire

property is valued at about $1,000. It is not considered at all probable

that any attempt is to be made to establish any such institution here,

but the Council decided to take prompt action in case there was anything

to the rumor, and the ordinance will successfully block the scheme.”

at this time, is the report recently in circulation that the Laurens

homestead, a desirable location in the center of town, and near the

campus of Randolph-Macon College, was to be purchased and converted

into a branch of the Tuskegee Institute for Negroes. On the Laurens

grounds at present is a small-two story frame building and the entire

property is valued at about $1,000. It is not considered at all probable

that any attempt is to be made to establish any such institution here,

but the Council decided to take prompt action in case there was anything

to the rumor, and the ordinance will successfully block the scheme.”

If Miriam Pierce was the frustrated owner of a dilapidated property that she wished to sell,

the fear tactics that she used were familiar to Southerners and resonated loudly within

the small town. The story of the school rumor was also carried in black newspapers,

such as The Appeal, a Midwestern African- American publication with offices in

Chicago and Minneapolis. New Yorkers would have also read about it in the Sun

newspaper on September 12th, which quoted a town resident saying, “We will never

allow a negro boarding school to be established in this town…”

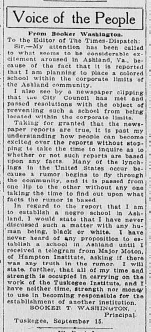

The news of the rumor and the hastily passed segregation ordinance was traveled far enough to

reach Booker T. Washington, who wrote a letter to the editor of the Richmond Times-Dispatch

that was published seven days after the news broke.

From Booker Washington

To the Editor of the Times-Dispatch

Sir- My attention has been called to what seems to be considerate excitement

around in Ashland, Va., because of the fact that it is reported that I am planning

to place a colored school within the corporate limits of the Ashland Community.

around in Ashland, Va., because of the fact that it is reported that I am planning

to place a colored school within the corporate limits of the Ashland Community.

I also see by a newspaper clipping that the City Council has met and passed

resolutions with the object of preventing such a school from being built within

the corporate limits.

resolutions with the object of preventing such a school from being built within

the corporate limits.

Taking for granted that the newspaper reports are true, it is past my understanding

how people can become excited over the reports without stopping to take the

time to inquire as to whether or not such reports are based upon any facts. Many

of the lynchings in the United States occur because a rumor begins to fly through

the community, and it is passed from one lip to the other without anyone taking

the time to find out upon what facts the rumor is based.

how people can become excited over the reports without stopping to take the

time to inquire as to whether or not such reports are based upon any facts. Many

of the lynchings in the United States occur because a rumor begins to fly through

the community, and it is passed from one lip to the other without anyone taking

the time to find out upon what facts the rumor is based.

In regard to the reports that I am to establish a negro school in Ashland,

I would state that I have never discussed such a matter with any human being,

black or white. I have never heard of any propositions to establish a school in

Ashland until I received a telegram from Major Moton of Hampton Institute

asking if there was any truth to the rumor. I will state further, that all of my

time and strength is occupied in carrying on the work of the Tuskegee Institute,

and I have neither time, strength, nor money to use in becoming responsible for

another institution.

I would state that I have never discussed such a matter with any human being,

black or white. I have never heard of any propositions to establish a school in

Ashland until I received a telegram from Major Moton of Hampton Institute

asking if there was any truth to the rumor. I will state further, that all of my

time and strength is occupied in carrying on the work of the Tuskegee Institute,

and I have neither time, strength, nor money to use in becoming responsible for

another institution.

Booker T. Washington

Principal

Tuskegee, September 15

Regardless of Miriam Pierce’s motives for spreading the rumor, the town leaders in Ashland

acted swiftly and did not wait to hear from Mr. Washington. 1911 was a popular year for

residential zoning laws that restricted where people could live based on the color of their skin.

Baltimore had become the first city in the US to pass such a law in December of 1910 and

Richmond had followed close behind in April of 1911.

acted swiftly and did not wait to hear from Mr. Washington. 1911 was a popular year for

residential zoning laws that restricted where people could live based on the color of their skin.

Baltimore had become the first city in the US to pass such a law in December of 1910 and

Richmond had followed close behind in April of 1911.

The Ashland Town Council elections in June of 1910 found nine white men serving in

leadership roles for the community: H.A. Ellett, Town Sergeant, C.W. Crew, Mayor;

Callom B. Jones, III, Mayor Pro Tempore, D.B. Cox, W.S. Brown, S.J. Doswell,

G.F. Delarue, W.L. Foy, and E.W. Newman. Ashland would elect their first woman

member of Town Council in 1946, and the first black person in 1977.

leadership roles for the community: H.A. Ellett, Town Sergeant, C.W. Crew, Mayor;

Callom B. Jones, III, Mayor Pro Tempore, D.B. Cox, W.S. Brown, S.J. Doswell,

G.F. Delarue, W.L. Foy, and E.W. Newman. Ashland would elect their first woman

member of Town Council in 1946, and the first black person in 1977.

The Ashland segregation ordinance was very similar to the ordinance that had been

passed in Richmond a few months earlier. It prohibited whites and blacks from living

on a block where they would have been in the minority. If a block had mostly white people

living on it, then a black person could not reside there. Those who passed the ordinance could

claim that they were being fair because the prohibited housing law applied equally to both

blacks and whites. It did make exceptions for people living in homes as servants, and it did

not prevent people from purchasing a property- they just couldn’t live in the house that they

owned.

passed in Richmond a few months earlier. It prohibited whites and blacks from living

on a block where they would have been in the minority. If a block had mostly white people

living on it, then a black person could not reside there. Those who passed the ordinance could

claim that they were being fair because the prohibited housing law applied equally to both

blacks and whites. It did make exceptions for people living in homes as servants, and it did

not prevent people from purchasing a property- they just couldn’t live in the house that they

owned.

Unfortunately, the climate in Ashland that feared a black college had been established years

earlier following the destruction caused by the Civil War. Because of its location just north of

Richmond, the capital of the Confederacy, and along the main supply lines of the railroad,

Ashland played a vital role during the war. The small town was used as a staging ground for

troops, a depot for supplies, and as a refugee settlement for people fleeing the fighting in

Richmond, and north in Fredericksburg. Many homes along the railroad tracks were used as

makeshift hospitals, and there were over 400 unnamed Confederate soldiers buried in the

town cemetery.

earlier following the destruction caused by the Civil War. Because of its location just north of

Richmond, the capital of the Confederacy, and along the main supply lines of the railroad,

Ashland played a vital role during the war. The small town was used as a staging ground for

troops, a depot for supplies, and as a refugee settlement for people fleeing the fighting in

Richmond, and north in Fredericksburg. Many homes along the railroad tracks were used as

makeshift hospitals, and there were over 400 unnamed Confederate soldiers buried in the

town cemetery.

No comments:

Post a Comment